Learning Environment Design Project

Flipping EDPT 502 Learning and Individual Differences

Introduction

Upon careful review of the EDPT 502 Learning and Individual Differences course at the University of Southern California (USC) Rossier School of Education (RSOE), the instructor determined that its general structure and specific learning tasks would benefit from revision.

- EDPT 502 represents a foundational course in USC RSOE’s Master of Education in Educational Counseling (EC) program, which aims to blend “a counseling-based theoretical foundation with practical applications in student affairs to prepare practitioners who promote and facilitate educational attainment” (“ME in Educational Counseling”, 2017, para. 1).

- Included in this revision is a redesign of course’s learning environments based on learner characteristics and course objectives.

- The redesigned EDPT 502 utilizes flipped classroom instruction, requiring the use of both virtual and physical learning environments.

Instructional Needs Assessment

Identifying the Need for Revision

Insights from course evaluations and the current instructor have revealed a few areas in the course that would benefit from revision.

- Optimize Instructional time: According to the course’s current instructor, too much time is spent in class building the learners’ prior knowledge around each respective unit’s content. This necessitates that learners spend much of their time in class for direct instruction with less time for practice and feedback, which is essential for the transfer of new conceptual and procedural knowledge (Smith & Ragan, 2005).

- Promote Mental Effort: The current instructor also found that learners may not have engaged enough with the material prior to class, as they appeared unprepared to participate in higher level or generative learning activities. This indicated that learners were applying inadequate mental effort to their course preparations. Given that mental effort is a behavioral indication of motivation, this lack of engagement may represent a motivational problem within the course.

Flipped Classroom Instruction

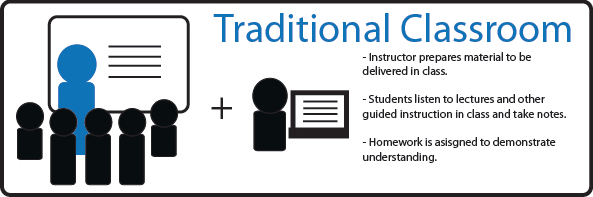

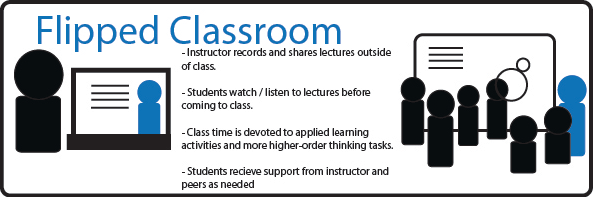

It has been determined that these problems can be resolved by utilizing flipped classroom instruction (FCI):

- FCI is an emerging blended learning pedagogy that exposes learners to new content on their own time before class, often through digital presentations (Bhagat, Chang, & Chang, 2016; Missildine, Fountain, Summers, & Gosselin, 2013; Zainuddin & Halili, 2016).

- This imparts learners with essential prior knowledge of the content before they attend class, allowing instructors to use time in class for active, meaningful learning (e.g. projects, simulations, collaborative work).

- This revision will enable learners to come to class ready to participate in active, collaborative engagement with the course material.

Discrepancy Model

The discrepancy needs assessment model is an appropriate choice for this course revision. Smith and Ragan (2005) describe the discrepancy model as a summative evaluation that assesses a course’s outcomes against its goals to determine if any significant gaps exist. Essentially, the discrepancy model measures “what is” versus “what should be” (p. 47).

Using the discrepancy model to evaluate past iterations of EDPT 502 has helped reveal gaps between its high-level learning outcomes and the actual learning that has taken place, including

- time students spend engaged in high versus low level learning activities;

- student engagement with the material prior to attending live sessions; and

- student evaluations that indicate a need to do more contextual work around diversity, access, and inclusion that could enrich the course’s content and better align its outcomes with RSOE’s mission in urban education.

Context of the Problem

This redesign of EDPT 502 takes place within the context of the USC RSOE. RSOE’s mission in urban education strives to improve “academic achievement and development in schools for urban students” (“EDPT 502 Syllabus,” 2017, p. 1).

The EC program is designed for individuals seeking careers in “two- and four-year postsecondary institutions, with a focus on academic counseling and advising” (“ME in Educational Counseling”, 2017, para. 1).

Like all courses at RSOE, EDPT 502 strives to further the school’s mission in urban education. Specifically, it provides candidates with a theoretical framework with which they can “critically examine learning and teaching in urban settings within the context of learning and cognitive development” (“EDPT 502 Syllabus”, 2017, p. 1).

Learner Characteristics

Cognitive Characteristics

All learners admitted into the EC program have graduated college and have the requisite graduate level reading skills and technical abilities to succeed in the course. Learners have demonstrated in previous courses the ability to work independently and collaboratively, participate in discussions, actively listen, and follow written and oral directions.

Being in the second semester of the program, all learners will have experience accessing and using the virtual learning environment and should have requisite prior knowledge necessary to meet all of the course’s technical requirements.

Prior knowledge related to course content and the ability to complete learning tasks varies by learner. All learners will have taken foundational courses related to educational counseling in the previous semester and many have experience working in educational counseling environments or, more broadly, the educational field. However, for many learners, this will be the first exposure to learning and motivation theory and meaningful learning strategies.

Developmental Considerations

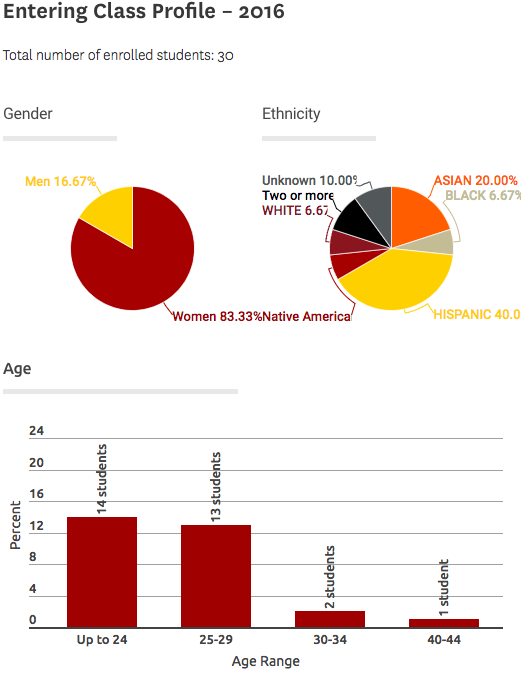

The vast majority of learners are considered young adults.

- This is a period marked by independence and self-discovery.

- Theorists such as Piaget assert that individuals in this developmental period are in an advanced formal operational stage of thinking, meaning that they can think in logical, abstract, nuanced, and idealistic ways that build on their accumulated knowledge and experience (see Santrock, 2016).

- Sinnot (2003), on the other hand, suggests that those in early adulthood have entered a stage of postformal thought, which is characterized by realistic, pragmatic, and reflective thinking.

One learner from the 2016 program was between the ages of 40-45, which is the developmental period of middle adulthood.

- At this stage, individuals find that some cognitive abilities continue to improve while others begin to decline (Santrock, 2016).

- At this stage, individuals find that some cognitive abilities continue to improve while others begin to decline (Santrock, 2016).

- At this stage, individuals find that some cognitive abilities continue to improve while others begin to decline (Santrock, 2016).

Motivation

Learners’ self-efficacy varies from person-to-person but is likely to increase over the course of the semester. Being only their second semester in a graduate program, learners are still fairly new to graduate level scholarly work and writing, and may exhibit some nervousness around course content and assignments. Alternatively, learners have experienced one semester of graduate school and should be better prepared to take on the more advanced work.

Individuals who enter the EC program come from diverse, often underrepresented backgrounds and seek to help others who have had similar experiences. These learners see themselves helping others with similar upbringing navigate their educational journey. As such, they have a high level of attainment value for completing this course and the EC program. They also have high utility value for course content, as it provides them with theoretical knowledge around learning and motivation that will be highly useful to them as they seek to improve learning outcomes for individual students and families.

Social Characteristics

Having gone through the previous semester of classes together, it is likely that there will be varying degrees of connections among individuals in the cohort. The level of connectedness that individuals feel to the cohort may impact their motivation to engage in course content and activities.

Having similar backgrounds to the populations that they seek to serve motivates students to actively engage in the course content in an effort to transfer skills and knowledge to their practice. These learners are at a place where they want to make a meaningful difference in the lives of students and their communities.

Demographic Data

At the time of writing, demographic data is only available for the Spring of 2016 cohort. Figure 1 displays the cohort’s demographic data, which, according to the instructor, is similar to previous cohorts. This diverse group of young learners seeks to serve communities that largely reflect their own backgrounds.

Stakeholders

Organizational stakeholders include the EC program faculty, staff, students, and the students’ social networks (e.g. students, organizations, colleagues). Additional stakeholders include all individuals associated with USC RSOE and its surrounding community.

Design of Learning Environment

This section will provide an overview and analysis of EDPT 502’s learning environments, their goals and objectives, and typologies. It will then go on to describe the evidence-based design decisions being made to optimize learning in the course’s given environments.

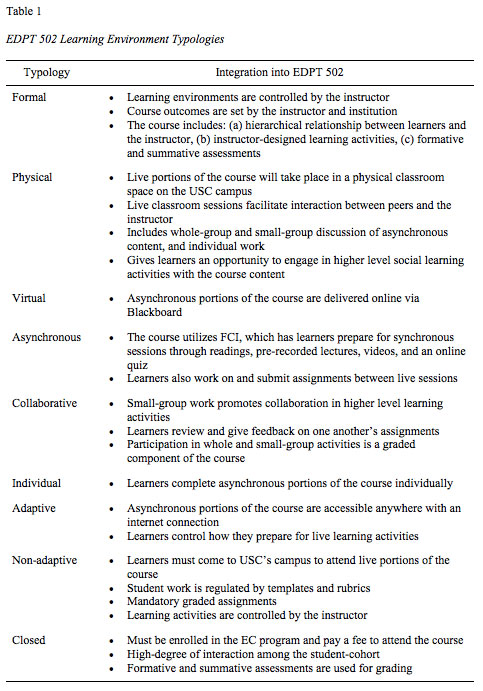

Description of the Learning Environment

As noted previously, EDPT 502 will utilize FCI, a blended learning format that involves both asynchronous and live (synchronous/physical) environments. In EDPT 502, learners will access asynchronous course content and activities through the Blackboard LMS prior to attending live sessions in a physical environment on the USC campus. Table 1 (p. 14-15) provides an overview of EDPT 502’s learning environment typologies.

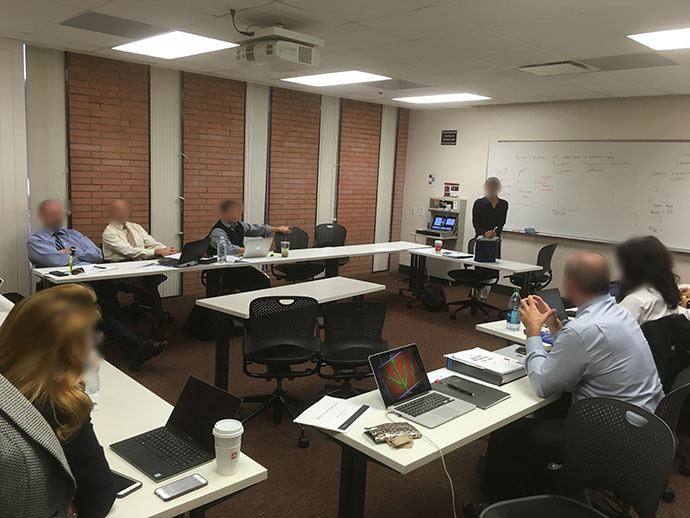

EDPT 502’s physical environment consists of a classroom located in Waite Phillips Hall on the USC campus, pictured. Note that

- the student tables and chairs are adjustable and on wheels to promote movement and flexibility.

- the rectangular tables can comfortably accommodate two people.

- the classroom has a dry erase board that doubles as a projector screen for presentations and USC Wi-Fi access for the instructor and student use.

Also note that

- the classroom is overcrowded with desks and chairs that cannot be removed.

- the classroom has very few wall outlets, limiting the ability to charge numerous devices

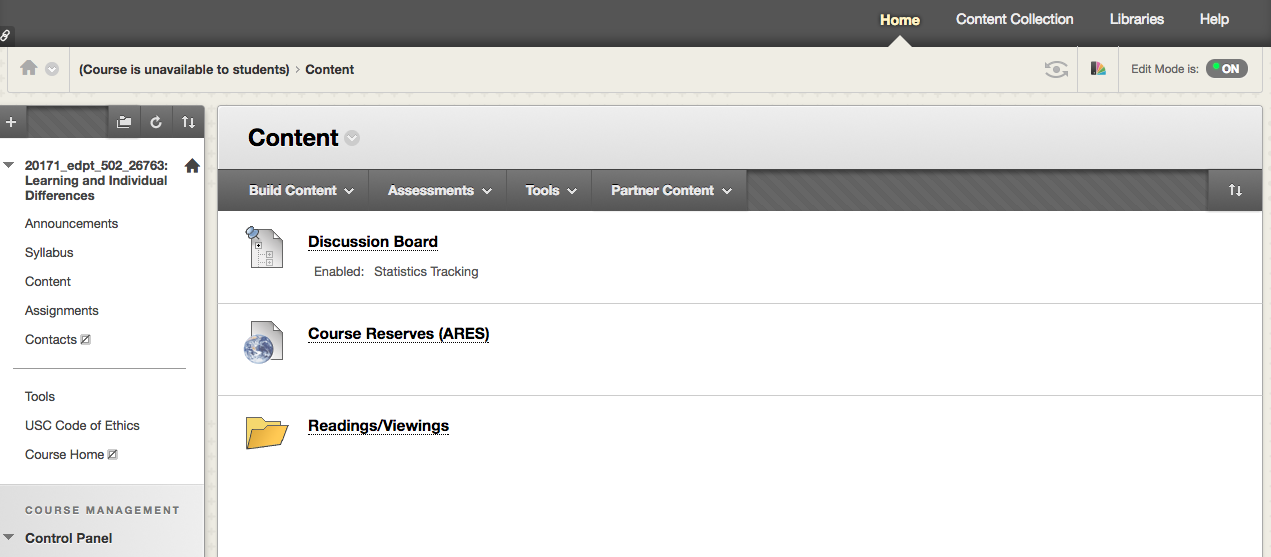

EDPT 502 will present all asynchronous content and assignments to students via the Blackboard LMS. Students can access Blackboard through any web browser on an internet-connected device. This access brings students to course content items such as:

- files

- folders

- URLs

- multimedia presentations

- assessment and evaluation items

- course assignments

- discussion board forums

The virtual environment does include a few constraints, including that

- learners must have internet connection with a reliable computer to access asynchronous content and assignments.

- learners, the instructor, and instructional designers have no flexibility in the medium they use to access course content.

Learning Environment Design Decisions

This section will analyze the available resources available in EDPT 502 learning environments, using scholarly work to justify design decisions.

The first major decision for EDPT 502’s learning environments is to use blended formats. The use of blended learning environments for EDPT 502 takes advantage of the best aspects of both virtual and physical learning environments.

Unfortunately, the physical environment, pictured in Figure 1 does not offer much design flexibility outside of how to manipulate the desks in the room.

- During whole-group activities, desks will be arranged in a horseshoe around the classroom, as pictured in Figure 1. Setting up the desks so that learners are facing each other will decentralize the classroom while promoting community and social presence. Bickford and Wright (2006) suggest that learning communities promote social interaction and knowledge construction.

- For small-group work, learners will be able to move desks around to create a comfortable workspace. According to Chism (2006), allowing learners the flexibility of moving tables and chairs to suit their needs promotes higher-level knowledge construction.

EDPT 502’s Blackboard LMS, pictured in Figure 2, represents the “flipped” portion of the course.

- Students will view recorded lectures in the form of screencast Adobe Captivate presentations or recorded video interviews with professionals in the field of educational counseling and learning and motivation.

- Online quizzes will be created and presented via Blackboard using either multiple choice or true/false items. These assessments are easily accessed by students and the instructor via the LMS and scored automatically.

- Figure 2 shows a weekly content page, which has a discussion board for learners to share ideas and answer discussion prompts, a link to access course readings, and a folder with weekly readings and viewings. Hrastinski (2008) posits that the flexibility of asynchronous learning environments allows learners to process more information, as they are able to access essential content at their own convenience and pace, which promotes individual learning.

- The use of a discussion board will allow learners to thoughtfully interact with one another through well-composed postings (Hrastinski, 2008). Discussion board postings will stem from structured prompts provided by the instructor, encouraging collaboration in the asynchronous environment while increasing its sociability, or conduciveness to social interaction (Ghosh, Rude-Parkins, & Kerrick, 2012).

Connection to the Pillars

This section of the paper will discuss how the design of EDPT 502’s learning environment connects to USC RSOE’s four academic pillars of Learning, Diversity, Accountability, and Leadership.

Connections to Learning

- EDPT 502’s course content is designed to provide learners with the foundational knowledge and skills necessary to apply the Learning pillar to their practice as aspiring educational counselors.

- The use of FCI in a blended learning environment will ensure that learners can handle the heavy cognitive load presented by this content.

Connections to Diversity

- Generative learning strategies foster learner-centered activities that allow learners to express themselves openly and learn from one another’s perspectives.

- Tables and chairs on wheels in the physical environment enables learners to organize themselves into collaborative groups.

- Flexible furniture also allows learners to adjust the environment according to their individual and group needs.

Connections to Accountability

- By the end of the course, learners should be able to assess and evaluate students to accurately diagnose learning and motivation problems while also applying evidence-based interventions to solve those problems.

- Learners will be required to take a pre and post knowledge survey to measure the course’s success in meeting its learning objectives.

Connections to Leadership

- Learners will have opportunities to learn and apply leadership strategies towards creative problem-solving initiatives.

- Collaborative activities in the learning environment enable learners to create and sustain partnerships.

References

Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl, D.R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review,84(2), 191-215. doi:10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191

Bhagat, K. K., Chang, C., & Chang, C. (2016). The impact of the flipped classroom on mathematics concept learning in high school. Educational Technology & Society, 19(3), 134-142. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.libproxy1.usc.edu/stable /jeductechsoci.19.3.134

Bickford, D. J. & Wright, D. J. (2006). Human-centered design guidelines. In D. G. Oblinger (Ed.), Learning Spaces (pp. 10.1-10.13). EDUCAUSE. OECD. (2010). 21st Century Learning Environments.

SourceChism, N. V. N. (2006). Human-centered design guidelines. In D. G. Oblinger (Ed.), Learning Spaces (pp. 10.1-10.13). EDUCAUSE. OECD. (2010). 21st Century Learning Environments. Source

Class Profile. (2016). Retrieved from Source

EDPT 502 syllabus. (2017). EDUC 502: Learning and Individual Differences [Syllabus]. Los Angeles, CA: Rossier School of Education, University of Southern California.

EDPT 502 midterm evaluation. (2017). EDPT 502 Learning and Individual Differences.

Individual report for Instructor. (2017). EDPT 502 Learning and Individual Differences.

Gee, L. (2006). Human-centered design guidelines. In D. G. Oblinger (Ed.), Learning Spaces (pp. 10.1-10.13). EDUCAUSE. OECD. (2010). 21st Century Learning Environments.

SourceGhosh, R., Rude-Parkins, C., & Kerrick, S. A. (2012). Collaborative Problem-Solving in Virtual Environments: Effect of Social Interaction, Social Presence, and Sociability on Critical Thinking (L. Moller & J. B. Huett, Eds.). The Next Generation of Distance Education, 191-205. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-1785-9_13

Hrastinski, S. (2008). Asynchronous and synchronous e-learning. Retrieved from Source

Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-Based Learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157-163. doi:10.1177/0963721412443552

ME in Educational Counseling. (2017). Retrieved from Source

Mayer, R. E. & Clark, R. C. (2011). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. (3rd ed.). Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA.

Missildine, K., Fountain, R., Summers, L., & Gosselin, K. (2013). Flipping the classroom to improve student performance and satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Education, 52(10), 597-599. doi:10.3928/01484834-20130919-03

Rossier’s Four Academic Pillars. (2017). Retrieved from Source

Zainuddin, Z., & Halili, S. H. (2016). Flipped classroom research and trends from different fields of study. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(3). doi:10.19173/irrodl.v17i3.2274